U.S. May Force California to Call More School Districts Failures

By Duke Helfand, Times Staff Writer

The Bush administration is pressing California to toughen its rules for

identifying failing school districts — a change that could add 310 school

systems to a watch list this year and eventually threaten the jobs of

superintendents and school board members throughout the state.

The U.S. Department of Education warned that it could cut off money to the state if California did not change the way it classified struggling districts under the No Child Left Behind Act.

The federal law calls for states to place districts on a watch list if the number of students doing well on math and English standardized tests fails to increase enough two years in a row. Such districts can face sanctions if they continue to falter.

California, however, lets districts avoid the list if students from low-income households reach a set score on a separate measure of achievement.

Federal education officials believe the state policy amounts to an escape valve. The policy violates No Child Left Behind by reducing the number of districts identified as needing improvement, the officials have told the state Department of Education.

Only 14 of California's 1,000 school districts were placed on the state's watch list this year.

But hundreds of districts could be considered failures within two years if California yielded to Washington's demands, according to state education officials.

The expanded list would feature some of California's highest-performing school districts, including Santa Monica-Malibu Unified and Cupertino Union near San Jose. Even though these districts are well regarded, they could still find themselves publicly labeled as troubled if certain groups of their students — those in special education, for example — were not making enough progress.

At the extreme, these school systems and the others could be abolished or restructured, or their superintendents and school board members could be replaced by state-appointed trustees.

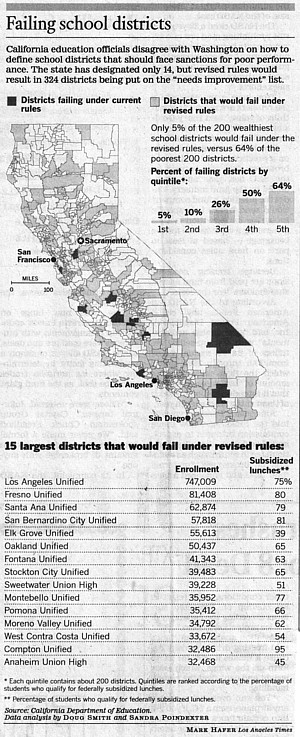

| California education officials disagree with Washington on how to define school districts that should face sanctions for poor perform-ance. The state has designated only 14, but revised rules would result in 324 districts being put on the "needs improvement" list. Only 5% of the 200 wealthiest school districts would fail under the revised rules, versus 64% of the poorest 200 districts. Percent of failing districts by quintile (Each quintile contains about 200 districts. Quintiles are ranked according to the percentage of students who qualify for federally subsidized lunches).:

|

Leaders of several California school systems said it would be unfair to identify failing districts in the middle of the school year without any notice or time to respond. The district officials wondered where the money would come from to create new programs aimed at improving student test scores.

"The entire notion of how No Child Left Behind has been enacted is very narrow, very myopic and very draconian," said Santa Monica-Malibu Unified Supt. John Deasy. "It sets up a very negative dynamic for schools that have successfully shown they can raise achievement over time."

No Child Left Behind requires schools to give standardized English and math tests annually in the third through eighth grades, and to increase the numbers of students who score high enough to be labeled proficient. The law calls for states to set annual improvement goals and to identify schools and districts as in need of improvement if they fall short.

State leaders say they have neither the money nor staff to oversee hundreds of districts that could fall under new scrutiny. And they question whether widespread failure would reduce No Child Left Behind to a meaningless federal mandate.

"What kind of an accountability system do you have when most of the school districts need help?" asked California Supt. of Public Instruction Jack O'Connell. "Frankly, we don't have the resources for that."

15 largest districts that would fail under revised rules * Percentage of students who qualify

for federally subsidized lunches. |

He and other state education officials have been lobbying the federal Education Department to ease its demands but have met with little success.

The two sides spoke Wednesday, but the dispute remains unresolved. Federal officials stood firm in their demand that the state ratchet up its system of identifying struggling schools, according to those involved in the conversation.

Federal education officials would not elaborate on the negotiations or say if they had made similar demands of other states.

Education Department spokeswoman Susan Aspey would say only that "our monitoring turned up some problems with the way the state identifies its districts that need improvement. We're working with California to resolve this issue."

In the meantime, the state Education Department this week notified 310 school systems, including those in Los Angeles, Santa Ana, Pomona and San Bernardino, that they could soon join the 14 districts already on the watch list.

Los Angeles Unified officials voiced anger at the prospect of a failure label.

"We're making real progress. We have been moving the ball down the court faster than most schools in California," said Supt. Roy Romer. "People should be applauding that and assisting us, not saying, 'We're going to cut your legs off.' They ought to give us assistance to improve. This redefinition is just not helpful."

He also objected to federal rules which say that if a district is on the watch list, it cannot provide supplemental tutoring to students who attend low-performing schools.

No Child Left Behind requires districts that are not on the list, but that have low-performing schools, to provide tutoring. L.A. Unified is spending about $25 million of its federal money to offer after-school tutoring to more than 16,000 students.

But if the district were put on the watch list, students would have to go elsewhere for tutoring — to private companies, for example.

Members of the Los Angeles Board of Education will hold a hearing today to discuss that issue and other challenges posed by No Child Left Behind.

Board members said they were concerned that a negative rating for the district would dampen enthusiasm at schools and further erode support for public education.

"It's a stigma that doesn't drive thoughtful change. It's controlling and punitive rather than encouraging," said David Tokofsky, who chairs the board committee holding today's hearing.

Officials in Santa Ana Unified said adding the district to the list of failures would ignore the district's success in recent years in raising test scores of low-performing students.

Redefining Santa Ana as a failing district in the middle of the year would also put teachers and students in an unfair predicament, officials said.

"It would obviously be very distressing," said Michele LePatner, interim director of research and evaluation for the district of more than 60,000 students. "It is very hard for us to monitor our students' progress when we don't know what the guidelines are and they are shifting as we go."

The controversy surfaced last fall, when federal education officials visited California to monitor how the state was implementing No Child Left Behind. The officials found several problems with application of the law, but the thorniest issue revolved around the identification of failing school districts.

Since December, the two sides have been negotiating. State Supt. O'Connell and state Board of Education President Ruth Green may travel to Washington next month in an effort to broker a compromise.

"There are obviously some issues we have to work out," Green said. "We want to approach them in a constructive way to find common ground."

Times staff writer Joel Rubin contributed to this report.